(Superior Court, Judge Gregory Weeks, April 22, 2012)

The first ruling under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act

Read the complete opinion.

Discrimination in jury selection frustrates the commitment of African-Americans to full participation in civic life. One of the stereotypes particularly offensive to African-American citizens is that they are not interested in seeing criminals brought to justice. African-Americans who have been excluded from jury service on account of race compare their experiences to the injustice and humiliations of the Jim Crow era.

(All blockquotes are taken from Judge Weeks’ ruling.)

UPDATE: The Racial Justice Act was repealed by the legislature in 2013. In December 2015, the North Carolina Supreme Court vacated the decisions in North Carolina v. Robinson and three subsequent cases in which defendants’ death sentences had been reduced to life, holding that the state had not been given sufficient time to review and respond to the studies on racial bias in jury selection. The case has been assigned to a new Senior Judge, since Judge Weeks has retired. The Supreme Court did not take a position on the merits of Judge Weeks’ ruling that race had been a significant factor in the death sentences of the four defendants.

Introduction

Background on the Racial Justice Act

Under the Racial Justice Act (RJA), a capital defendant can have his or her sentence reduced to life in prison without parole if there is evidence proving “that race was a significant factor in decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed.” (N.C. Gen. Stat. §15A-2010)

Defendants may present evidence in three categories:

- Evidence that death sentences were sought or imposed more frequently upon defendants of one race than others

- Evidence that death sentences were sought or imposed more frequently on behalf of victims of one race than others, or

- Evidence that race was a significant factor in decisions to exercise peremptory strikes during jury selection

Any one of these three categories is sufficient to establish a RJA violation. Robinson presented evidence in the third category, peremptory strikes during jury selection. Peremptory strikes allow prosecutors and defense lawyers to remove members of the jury pool they believe may be unfavorable to their side. Each side is allowed a set number of peremptory strikes, which may not target venire members based on race or gender. Potential jurors who indicate bias in the case or cannot follow the applicable laws can be eliminated “for cause.” Strikes for cause are not included in the the evidence presented in this case.

Witnesses

Five witnesses testified on Robinson’s behalf, including the co-authors of a Michigan State statistical study examining whether race was a factor in jury selection in North Carolina.

Eight witnesses testified for the state, including six current or former North Carolina judges who presided over cases included in the statistical study, and a statistical expert who assisted the Georgia Attorney General in McCleskey v. Kemp.

To hold that a defendant cannot prevail under the RJA unless he proves intentional discrimination would read a requirement into the statute that the General Assembly clearly did not place there.

Statutory Interpretation of the Racial Justice Act

The court needed to determine the meaning of “significant” in order to find if race was a “significant factor” in Robinson’s case. Based on past North Carolina Supreme Court decisions, the court defined “significant” as “having or likely to have influence or effect.” Thus, the Court examined “whether race had or likely had an influence or effect on decisions to exercise peremptory strikes during jury selection in capital proceedings.”

For statistical evidence, the court required a probability of 5% or less that a statistical result is due to chance in order to demonstrate statistical significance of that result under the RJA.

Judge Weeks held that evidence of intentional discrimination is not required. “To hold that a defendant cannot prevail under the RJA unless he proves intentional discrimination would read a requirement into the statute that the General Assembly clearly did not place there.” In addition, the defendant does not have to prove discrimination in his or her particular case because the General Assembly excluded such a provision from the final version of the RJA.

The ruling also stated that defendants do not have to show prejudice, that is, they do not have to prove that the use of race affected the outcome of his or her case, or the final composition of the jury.

Post-Batson studies of jury selection in the United States show that discrimination against African-Americans remains a significant problem that will not be corrected without a conscious and overt commitment to change. The RJA is North Carolina’s commitment to change.

Statistical Evidence

Robinson presented a statistical study on jury selection conducted by two professors at the Michigan State University School of Law. The study consisted of two parts: an unadjusted study of race and strike decisions for 7,421 potential jurors drawn from 173 proceedings for North Carolina’s death row inmates in 2010, and a regression study of a 25% random sample of that group, analyzing whether alternative explanations affected the relationship between race and strike decisions. Additionally, a regression study was conducted of all possible jury members in the cases from Cumberland County, where Robinson was tried. For Cumberland County jurors and those in the random sample group, researchers examined additional data, including demographic characteristics other than race, prior experiences in the legal system, attitudes about the death penalty, and any stated bias or difficulty in following the applicable laws.

The court found the MSU study to be “a valid, highly reliable, statistical study of jury selection practices in North Carolina capital cases between 1990 and 2010. The results of the unadjusted study, with remarkable consistency across time and jurisdictions, show that race is highly correlated with strike decisions in North Carolina.”

Findings of the MSU Study

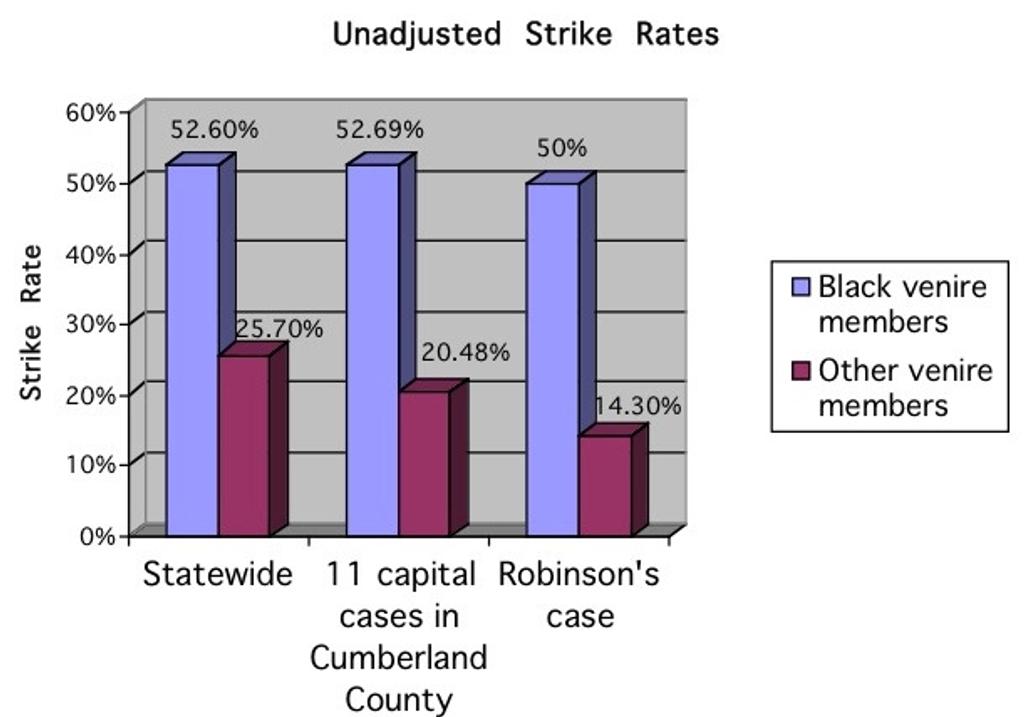

Based on the MSU study, the Court found that prosecutors statewide struck 52.6% of eligible black venire members, compared to only 25.7% of all other eligible venire members. The probability of this disparity occurring in a race-neutral jury selection process was less than one in ten trillion. (See p. 58 of Opinion).

The Court found that MSU’s unadjusted data were consistent with an inference that race was a significant factor in prosecutors’ use of peremptory strikes in North Carolina at the time of Robinson’s trial, in the Second Judicial Division at the time of Robinson’s trial, in Cumberland County at the time of Robinson’s trial, and in Robinson’s trial itself, permitting “an inference of intentional discrimination.”

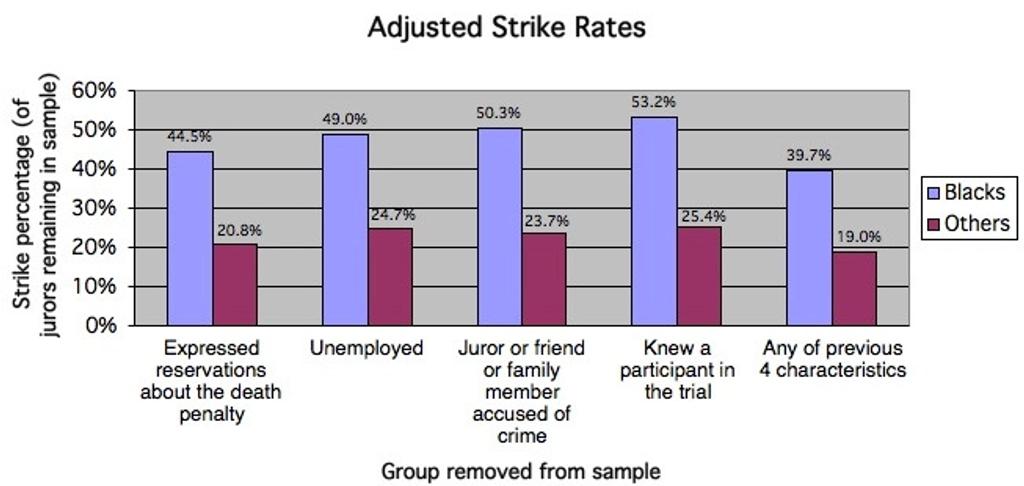

In the adjusted analysis, researchers identified four possible explanatory factors that were among the most common reasons given by prosecutors for exercising peremptory strikes. Some of the factors correlated with race, but were themselves race-neutral. They removed venire members with each characteristic from the sample, then analyzed strike patterns for the remaining sample. The four factors the researchers identified were: 1) any expressed reservations on the death penalty; 2) unemployment; 3) the venire member or a close relative had been accused of a crime; and 4) the venire member knew any trial participant. They also performed an analysis in which all venire members with any one of the four characteristics were removed.

Even in the adjusted samples, racial disparities were still observed:

The researchers also performed multiple logistic regression analyses to account for the effect of these and other factors, such as age, profession, and education. “O’Brien testified, and this Court finds as fact, that no regression analysis model with any combination of non-racial potential explanatory variables was ever identified that revealed the predictive effect of race to be attributable to any non-racial variable.” That is, even when researchers controlled for every identifiable variable, racial discrepancies were still found, showing as conclusively as possible that race was a factor in peremptory strikes.

In enacting the Racial Justice Act (RJA), the North Carolina General Assembly made clear that the law of North Carolina rejects the influence of race discrimination in the administration of the death penalty. The RJA represents a landmark reform in North Carolina, a state which has long been a leader in forward-thinking criminal justice policies.

Non-Statistical Evidence

Robinson and the State both presented non-statistical evidence, such as court transcripts and sworn affidavits. The Court found that the non-statistical evidence “overwhelmingly supports a finding that race was a significant factor in jury selection statewide, in the former Second Judicial Division, and in Cumberland County at the time of Robinson’s trial.”

Three witnesses testified about unconscious bias, noting that race influences decision-making processes at a subconscious level, and that those who are conscious of racial bias are reluctant to admit it.

The State’s statistical expert, Joseph Katz, testified about a prosecutor survey he conducted, in which he asked prosecutors to provide a race-neutral reason for the peremptory strikes of every African-American from the MSU study. He was able to collect responses for approximately half of the struck venire members. The Court criticized his survey for its poor methodology (requesting a race-neutral explanation, rather than asking why a specific juror was struck), his reliance on self-reported data, his close work with the State in designing and implementing the survey, and the fact that he circulated a sample affidavit to prosecutors, potentially skewing their responses. Additionally, the Court noted that the survey’s 50% non-response rate suggested that the non-responding prosecutors may have discriminated on the basis of race in selecting capital juries.

Included in the non-statistical evidence presented by Robinson were a number of case examples of discrimination. African-Americans, for example, were struck for membership in the NAACP or for attending a historically black university; some African-Americans were subjected to different questioning than other jurors; and some African-Americans were struck for what the Court called “patently irrational reasons,” such as past service in the U.S. Army or answering questions with “yeah.” Robinson also presented numerous instances when prosecutors struck African-American venire members for a seemingly objectionable characteristic but then accepted non-black venire members with comparable or even identical traits.

Three witnesses testified on the availability of training programs on how to minimize the effects of racial bias. In its closing argument, the State conceded that such trainings might be beneficial.

In the first case to advance to an evidentiary hearing under the RJA, Robinson introduced a wealth of evidence showing the persistent, pervasive, and distorting role of race in jury selection throughout North Carolina. The evidence, largely unrebutted by the State, requires relief in his case and should serve as a clear signal of the need for reform in capital jury selection proceedings in the future.

Conclusions

The Court concluded “that Robinson has established that race was a significant factor in decisions of prosecutors to exercise peremptory strikes in Cumberland County, the former Second Judicial Division, and in the State of North Carolina…from 1990 to 2010.” The ruling stated that Robinson’s statistical data, as well as the anecdotal and historical evidence presented by Robinson, showed patterns of discrimination, and that the State’s rebuttal was insufficient to rebut Robinson’s case.

Although the RJA does not require proof of discrimination in the defendant’s particular case, Judge Weeks found “that race was a significant factor in prosecutorial decisions to exercise peremptory strikes in Robinson’s capital trial.”

Robinson’s death sentence was vacated, and he was resentenced to life imprisonment without parole. The State may appeal Judge Weeks’ decision to the North Carolina Supreme Court. One hundred and fifty other death row inmates have filed challenges under the RJA, some claiming racial discrimination in the selection of cases, others claiming bias in jury selection.