United States Supreme Court

Public Statements by Justices on the Death Penalty

The following is an informal collection of statements by present or former Supreme Court Justices on the death penalty taken from interviews or essays, rather than from Court opinions.

Justice Stephen Breyer (Retired) on the Death Penalty

In his new book, The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities, and in media interviews accompanying its release, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer discusses the relationship between American laws and those of other countries and his dissent in Glossip v. Gross, which questioned the constitutionality of the death penalty. In an interview with The National Law Journal, Breyer summarized the core reasons underlying his Glossip dissent: “You know, sometimes people make mistakes, [executing] the wrong person. It is arbitrary. There is lots of evidence on that. Justice Potter Stewart said it was like being hit by lightning, whether the person is actually executed. If carried out, a death sentence, on average takes place now 18 years after it is imposed. The number of people who are executed has shrunk dramatically. They are centered in a very small number of counties in the United States. Bottom line is, let’s go into the issue. It is time to go into it again.” In his book, Breyer argues that the laws and practices of foreign countries are relevant to and might be particularly informative on questions regarding the Eighth Amendment. He notes that international opinion has influenced decisions to end the death penalty for juveniles and for crimes that do not result in death. His Glossip opinion also mentioned international practices - that only 22 countries carried out executions in 2013 and that the U.S. was one of only eight that executed more than 10 people - among the reasons American capital punishment may be an unconstitutionally “cruel and unusual punishment.” That phrase, he says in his book, is itself of foreign origin. “It uses the word ‘unusual,’” Breyer says, “and the founders didn’t say unusual in what context.” Foreign law and practices, he argues, should form part of that context.

(R. Teague Beckwith, “Supreme Court Justice Argues World Opinion Matters on the Death Penalty,” TIME, September 14, 2015; A. Liptak, “Justice Breyer Sees Value in a Global View of Law,” The New York Times, September 12, 2015; T. Mauro, “Q&A: Justice Breyer’s Interview With The NLJ,” The National Law Journal, September 12, 2015).

Other Earlier Statements:

“You have to understand that each death penalty case usually comes before the court three times. The average defendant is on death row for 15 years,” said Breyer.

He continued, “The recanting of witnesses is often raised. That is not enough. It is necessary to have proof that someone else has had to pull the trigger. There would have to be something really wrong for the Supreme Court to hear anything significantly new that was not heard before by the lower courts. We are presented with roughly the same arguments, just at the last minute.”

Breyer explained that the court can not rule on the death penalty itself or address the racial disparity of its imposition since “it is mostly imposed by state law, rarely federal law. Only the legislature can abolish the death penalty,” said Breyer.

Citing the example of French President Mitterand, Breyer utilized his bully pulpit to urge the executive and legislative branches to abolish the death penalty in America. “Europe is against the death penalty now,” he said. “In 1980, 2/3 of the French electorate supported the death penalty. Still Mitterand, in a television interview, came out against the death penalty. He immediately went up in the polls because he took a position of conscience. The same thing could happen here.”

He doubts that abolition of the death penalty will happen. “Politicians were in the popular club in high school. They hold their finger up to the wind to measure popularity,” opined Breyer. “Judges are terrible politicians.”

(Business Insider, October 21, 2011.)

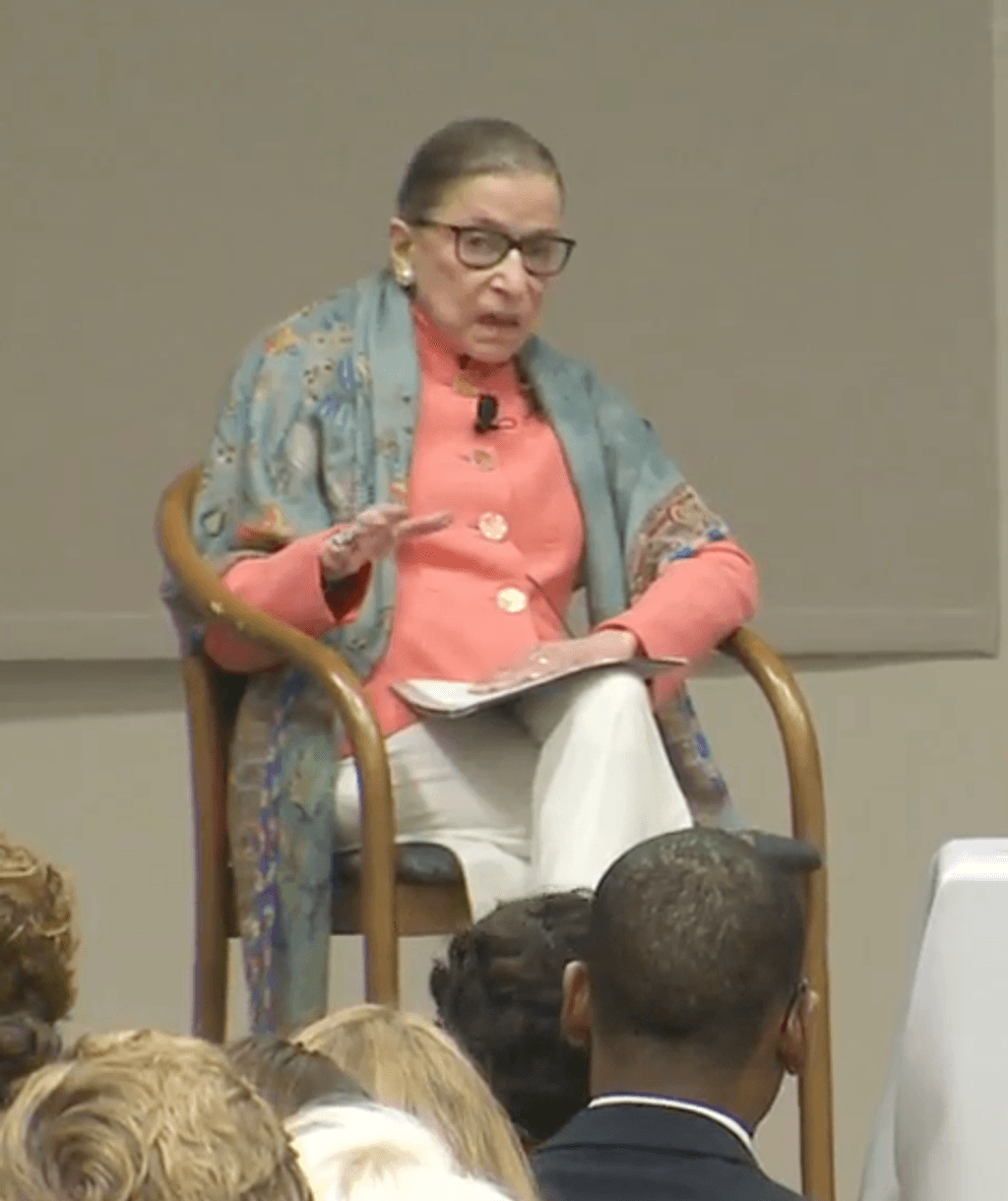

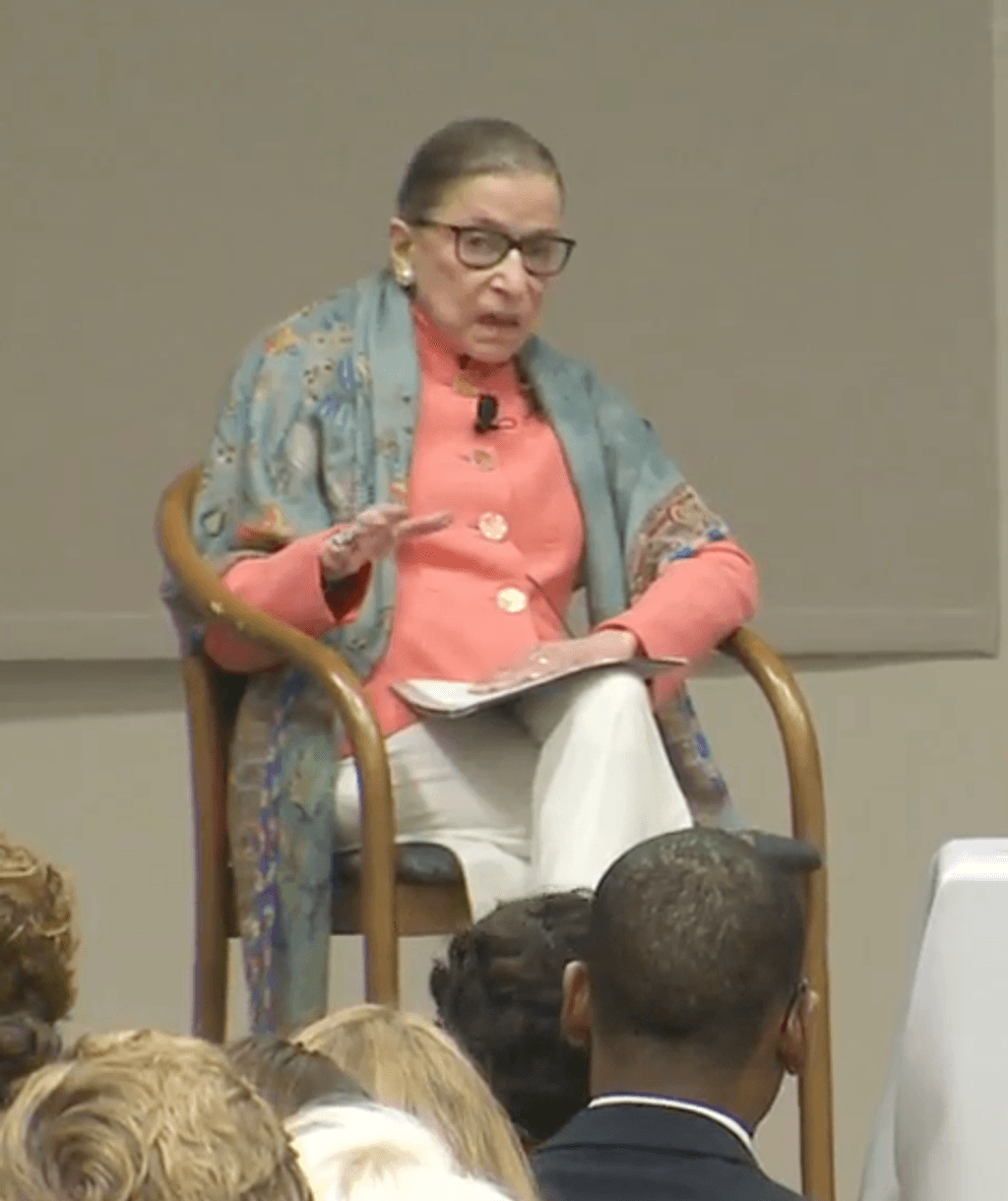

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Deceased) on the Death Penalty

Justice Ginsburg’s statement during Washington Council of Lawyers’ forum at George Washington University

Justice Ginsburg was asked about the future of the death penalty towards the end of a hour-hour public forum at George Washington University on July 24, 2017. She answered:

“The only comment I would make is that the incidence of capital punishment has gone down, down, down so that now, I think, there are only three states that actually administer the death penalty.

“And not even whole states, but particular areas of states. It may depend on who’s the district attorney.

“We may see an end to capital punishment by attrition as there are fewer and fewer executions.”

(Washington Council of Lawyers, 2017 Summer Forum with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, July 24, 2017; A. Liptak, On Justice Ginsburg’s Summer Docket: Blunt Talk on Big Cases, New York Times, August 1, 2017; K. Blakinger, Ruth Bader Ginsburg predicts possible end to capital punishment, Houston Chronicle, August 2, 2017. Photo credit, Screenshot from the Washington Council of Lawyers YouTube video of the summer forum.)

Justice Ginsburg’s comments during a talk at Stanford University

Justice Ginsburg fielded a question about the death penalty in connection with her February 6, 2017 appearance at the annual Rathburn Lecture on a Meaningful Life at Stanford University. She responded: “If I were queen, there would be no death penalty.”

(L. Krieger, Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg talks Congress, death penalty and “a meaningful life” at Stanford, The Mercury News, February 6, 2017; A. de Vogue, Ginsburg talks partisan rancor, Electoral College and kale, CNN, February 7, 2017.)

Ginsburg Interview with the National Law Journal (excerpt)

NLJ: Towards the end of their tenure on the court, justices Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens, and even later than that, Justice Lewis Powell Jr., decided they could no longer support the constitutionality of the death penalty. As we see increased problems with lethal injection, what are your thoughts now about the penalty?

GINSBURG: I’ve always made the distinction that if I were in the legislature, there’d be no death penalty. If I had been on the court for Furman [v. Georgia, 1972, invalidating the death penalty], I wouldn’t have given us the death penalty back four years later. Stevens and Powell were part of that. I think there wouldn’t have been a big fuss. There was a big fuss initially over the decision that stopped executions. If the court had stayed there, it would have been accepted. That was the golden opportunity. I had to make the decision was I going to be like Brennan and Marshall who took themselves out of the loop [by dissenting in every case upholding the penalty]. There have been some good death penalty decisions. If I took myself out, I couldn’t be any kind of contributor to those.

NLJ: After more than two decades on the court, what types of cases still vex or challenge you?

GINSBURG: Death penalty. For one thing, our jurisprudence is dense and then we have these contributions from Congress like AEDPA [Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act]. Because we had no death penalty in the District of Columbia, my first year here, I asked my clerks to write a memo so I could become familiar with where the court was on the death penalty. It was dense then and it has gotten only worse.

(M. Coyle, National Law Journal, Aug. 22, 2014).

Justice Ginsburg interview at Duke Law School after end of 2014 Court Term

In an interview at Duke Law School, Justice Ginsburg reflected on the Court’s 2014 court term and discussed Glossip v. Gross, in which she joined Justice Stephen Breyer in a dissent that questioned the constitutionality of the death penalty.

Ginsburg said she had waited to take such a stance on the death penalty because past justices, “took themselves out of the running,” when the did so, leaving, “no room for them to be persuasive with the other justices.” She reiterated many of the key points from the dissent, saying, “I think that [Breyer] pointed to evidence that has grown in quantity and in quality. He started out by pointing out that there were a hundred people who had been totally exonerated of the capital crime with which they were charged … so one thing is the mistakes that are possible in this system. The other is the quality of representation. Another is … yes there was racial disparity but even more geographical disparity. Most states in the union where the death penalty is theoretically on the books don’t have executions.”

Justice Ginsburg also noted the growing isolation of the death penalty. “[L]ast year, I think 43 of the states of the United States had no executions, only seven did, and the executions that took place tended to be concentrated in certain counties in certain states. So the idea that luck of the draw, if you happened to commit a crime in one county in Louisiana, the chances that you would get the death penalty are very high. On the other hand, if you commit the same deed in Minnesota, the chances that you would get the death penalty are almost nil. So that was another one of the considerations that had become clear as the years went on.”

(S. Lachman and A. Alman, “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Reflects On A Polarizing Term One Month Out,” The Huffington Post, July 29, 2015.)

Ginsburg Supports Abolition

If I had my way there would be no death penalty. But the death penalty for now is the law, and I could say ‘Well, I won’t participate in those cases,’ but then I can’t be an influence. Every time I have to participate in a case where someone has been sentenced to death, I feel that same conflict.

(Reuters, February 5, 2013.)

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, speaking to law students in San Francisco, at UC Hastings College of the Law:

The subject of capital punishment came up when Hastings Professor Joan Williams, who conducted the 90-minute question-and-answer session, asked the 78-year-old justice what she would like to accomplish in her remaining years on the court.

“I would probably go back to the day when the Supreme Court said the death penalty could not be administered with an even hand, but that’s not likely to be an opportunity for me,” Ginsburg said.

She was referring to the ruling in a 1972 Georgia case that overturned all state death penalty laws, which had allowed judges and juries to impose death for any murder. Four years later, the court upheld another Georgia law that prescribed death for specific categories of murder and gave guidance to juries, a model that California followed when it renewed capital punishment in 1977.

Ginsburg described review of impending executions as “a dreadful part of the business,” and said she has chosen not to follow the path of the late Justices Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan - who declared in every capital case that they considered the death penalty unconstitutional - so that she could maintain a voice in the debate.

(San Francisco Chronicle, September 16, 2011)

Justice Ginsburg Supports Moratorium

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recently voiced her support for a moratorium on the death penalty in Maryland and criticized the inadequate funding available for those who represent poor people. “People who are well represented at trial do not get the death penalty,” said Ginsburg. “I have yet to see a death case among the dozens coming to the Supreme Court on eve-of-execution stay applications in which the defendant was well represented at trial.”

(Associated Press, April 10, 2001)

Justice Anthony Kennedy on the Death Penalty (Retired)

During oral arguments at the Supreme Court one year apart in 2014 and 2015, Justice Kennedy asked counsel questions about death-row conditions of confinement that appeared unrelated to the issues raised in the cases:

In Hall v. Florida, 134 S. Ct. 1986 (2014) (No. 12-10882), transcript of March 3, 2014 argument available at http://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/12-10882…

JUSTICE KENNEDY: [T]he last ten people Florida has executed have spent an average of 24.9 years on death row. Do you think that that is consistent with the purposes of the death penalty, and … is it consistent with sound administration of the justice system?

MR. WINSOR [counsel for the State of Florida]: Well, I certainly think it’s consistent with the Constitution, and I think that there are obvious …

JUSTICE KENNEDY: That wasn’t my question.

MR. WINSOR: Oh, I’m sorry, I apologize.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Is it consistent with … the purposes that the death penalty is designed to serve, and is it consistent with an orderly administration of justice?

MR. WINSOR: It’s consistent with the …

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Go ahead.

MR. WINSOR: It is consistent with the purposes of the death penalty certainly.

JUSTICE SCALIA: General Winsor, maybe you should ask us … that question, inasmuch … as most of the delay has been because of rules that we have imposed.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Well, let me … ask this. Of course most of the delay is at the hands of the defendant. In this case it was 5 years before there was a hearing on the on the …Atkins question. Has the Attorney General of Florida *992 suggested to the legislature any … measures, any provisions, any statutes, to expedite the consideration of these cases.

MR. WINSOR: Your Honor, there was a statute enacted last session, last spring, that is—it’s called the Timely Justice Act, that addresses a number of issues that you raise, and it’s presently being challenged in front of the Florida Supreme Court… .

In Davis v. Ayala, 135 S. Ct. 2187 (2015) (No. 131428), from transcript of March 3, 2015 argument:

JUSTICE KENNEDY: This doesn’t relate to the issues you’ve been arguing. This crime was, what, 30 years ago and the trial 26 years ago?

MR. DAIN [counsel for death row inmate Hector Ayala]: 1996, yeah, very close.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Has he spent time in solitary confinement, and, if so, how much?

MR. DAIN: He has spent his entire time in what’s called administrative segregation. When I visit him, I visit him through glass and wire bars.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Is that a single cell?

MR. DAIN: It is a single cell. They’re all single cells. Well, San Quentin is on the most it’s on Heaven’s land in Marin County. It’s a 150-year-old prison and their administrative segregation is single cells, a very old system, very small, and — and —

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Is it the same thing as solitary confinement?

MR. DAIN: No, it’s 23 hours out of the day, that probably is the same. They generally administrative segregation you’re not allowed in the general yard anymore. But you are allowed an hour a day —

JUSTICE KENNEDY: One hour.

MR. DAIN: — of activity.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on the Death Penalty (Deceased)

Justice O’Connor Stresses Importance of International Law

During a speech hosted by the Southern Center for International Studies in Atlanta, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor stressed the importance of international law for American courts and the need for the United States to create a more favorable impression abroad. She cited recent Supreme Court cases, including the Court’s ruling to ban the execution of those with mental retardation, that illustrate the increased willingness of U.S. courts to take international law into account. “I suspect that over time we will rely increasingly, or take notice at least increasingly, on international and foreign courts in examining domestic issues.” O’Connor noted that doing so “may not only enrich our own country’s decisions, I think it may create that all important good impression.”

(World Net Daily, October 31, 2003)

Justice O’Connor Again Voices Concern About Innocence

At the Nebraska State Bar Association’s annual meeting, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor expressed her concern about the possibility of executing the innocent and the need for better representation of indigent defendants. O’Connor stated, “More often than we want to recognize, some innocent defendants have been convicted and sentenced to death.” She added that that would continue to happen unless indigent defendants were represented by qualified lawyers. Earlier this year, O’Connor expressed similar concerns about executing the innocent while speaking to the Minnesota Women Lawyers’ Group.

(Nebraska StatePaper.com, Oct. 19, 2001)

Justice O’Connor Questions Death Penalty

In a speech on July 2, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said there were “serious questions” about whether the death penalty is fairly administerd in the U.S. Noting the number of death row inmates who have been exonerated in recent years, O’ Connor stated, “If statistics are any indication, the system may well be allowing some innocent defendants to be executed.” She also addressed the need for quality representation in capital cases, stating that such representation has too often been inadequate. “Perhaps it’s time to look at minimum standards for appointed counsel in death cases and adequate compensation for appointed counsel when they are used,” she said. In speaking to the Minnesota Women Lawyer’s group, O’Connor also expressed her concern about the rising numbers of inmates on death row and of executions since her appointment to the Court. Noting that Minnesota does not have the death penalty, O’Connor said, “You must breathe a big sigh of relief every day.”

(Associated Press, July 2, 2001).

“More often than we want to recognize, some innocent defendants have been convicted and sentenced to death.” — U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor

Justice Antonin Scalia (Deceased) on the Death Penalty

Justice Scalia said he “wouldn’t be surprised” if the U.S. Supreme Court found the death penalty unconstitutional (Commercial Appeal, Sept. 22, 2015, speech at Rhodes College). He repeated those remarks at an appearance at the University of Minnesota Law School on October 20, 2015 (Associated Press, “Scalia: ‘Wouldn’t Surprise Me’ If Death Penalty Struck Down,” October 20, 2015).

Antonin Scalia - God’s Justice and Ours

In recent years, that philosophy has been particularly well enshrined in our Eighth Amendment jurisprudence, our case law dealing with the prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishments.” Several of our opinions have said that what falls within this prohibition is not static, but changes from generation to generation, to comport with “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” Applying that principle, the Court came close, in 1972, to abolishing the death penalty entirely. It ultimately did not do so, but it has imposed, under color of the Constitution, procedural and substantive limitations that did not exist when the Eighth Amendment was adopted—and some of which had not even been adopted by a majority of the states at the time they were judicially decreed. For example, the Court has prohibited the death penalty for all crimes except murder, and indeed even for what might be called run–of–the–mill murders, as opposed to those that are somehow characterized by a high degree of brutality or depravity. It has prohibited the mandatory imposition of the death penalty for any crime, insisting that in all cases the jury be permitted to consider all mitigating factors and to impose, if it wishes, a lesser sentence. And it has imposed an age limit at the time of the offense (it is currently seventeen) that is well above what existed at common law.

If I subscribed to the proposition that I am authorized (indeed, I suppose compelled) to intuit and impose our “maturing” society’s “evolving standards of decency,” this essay would be a preview of my next vote in a death penalty case. As it is, however, the Constitution that I interpret and apply is not living but dead—or, as I prefer to put it, enduring. It means today not what current society (much less the Court) thinks it ought to mean, but what it meant when it was adopted. For me, therefore, the constitutionality of the death penalty is not a difficult, soul–wrenching question. It was clearly permitted when the Eighth Amendment was adopted (not merely for murder, by the way, but for all felonies—including, for example, horse–thieving, as anyone can verify by watching a western movie). And so it is clearly permitted today. There is plenty of room within this system for “evolving standards of decency,” but the instrument of evolution (or, if you are more tolerant of the Court’s approach, the herald that evolution has occurred) is not the nine lawyers who sit on the Supreme Court of the United States, but the Congress of the United States and the legislatures of the fifty states, who may, within their own jurisdictions, restrict or abolish the death penalty as they wish.

But while my views on the morality of the death penalty have nothing to do with how I vote as a judge, they have a lot to do with whether I can or should be a judge at all. To put the point in the blunt terms employed by Justice Harold Blackmun towards the end of his career on the bench, when he announced that he would henceforth vote (as Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall had previously done) to overturn all death sentences, when I sit on a Court that reviews and affirms capital convictions, I am part of “the machinery of death.” My vote, when joined with at least four others, is, in most cases, the last step that permits an execution to proceed. I could not take part in that process if I believed what was being done to be immoral.

(Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life at the University of Chicago Divinity School, January 2002)

Here is a retrospective on Justice Scalia and the Death Penalty.

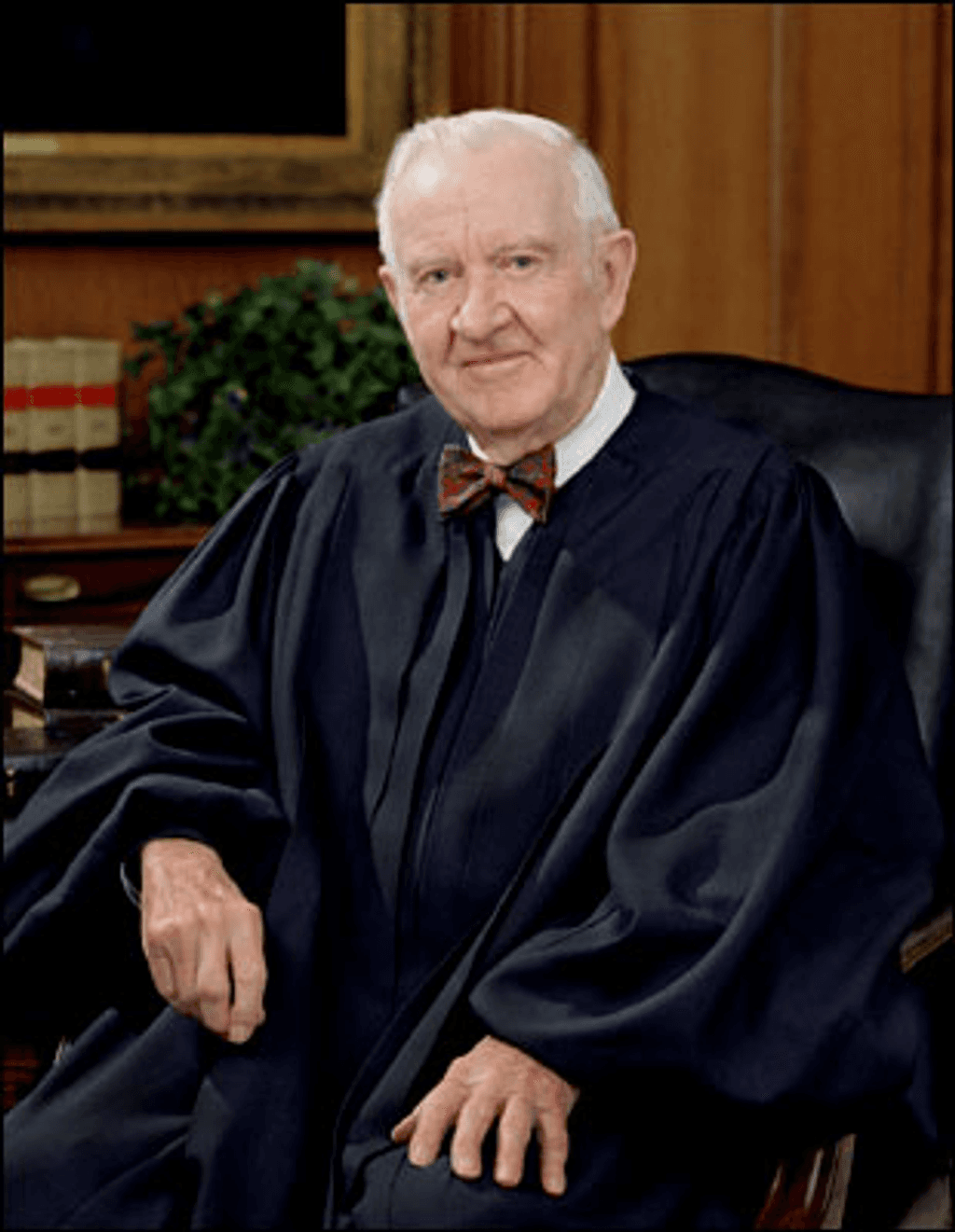

Justice John Paul Stevens (Deceased) on the Death Penalty

Video-taped comments by Justice Stevens to the California Attorneys for Criminal Justice Seminar, Feb. 20, 2016. Justice Stevens called for the abolition of the death penalty because of the risks of executing the innocent, its high costs relative to its questionable benefits, and the lengthy time defendants spend on death row. He suggested change could come from the Supreme Court on constitutional grounds, from state legislatures, and from governors granting commutations.

Comments by Justice Stevens at George Washington University, May 19, 2015.

Previous Comments:

On Innocence

In a discussion at the University of Florida Law School, former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens said that recent research reveals that Texas almost certainly executed an innocent man in 1989. Stevens said:

“Within the last year, Jim Liebman, who’s a professor at the Columbia Law School and was a former law clerk of mine, has written a book…called The Wrong Carlos…He has demonstrated, I think, beyond a shadow of a doubt that there is a Texas case in which they executed the wrong defendant, and that the person they executed did not in fact commit the crime for which he was punished. And I think it’s a sufficient argument against the death penalty…that society should not take the risk that that might happen again, because it’s intolerable to think that our government, for really not very powerful reasons, runs the risk of executing innocent people.”

Prof. Liebman’s research showed that Carlos DeLuna’s case involved faulty eyewitness testimony and police failure to investigate an alternative suspect.

(T. Nashrulla, “Former Supreme Court Justice Confirms Texas Once Executed An Innocent Man,” Buzzfeed News, January 26, 2015; video of John Paul Stevens’ discussion, quote begins at 57:00).

Justice Stevens on the Death Penalty

I really think that in regard to the death penalty … I’m not sure that the democratic process won’t provide the answers sooner than the court does, because I do think there is a significantly growing appreciation of the basic imbalance in cost-per-person benefit analysis. And the application of the death penalty does a lot of harm, and does really very little good.

(Daily Caller, April 22, 2012.)

Justice Stevens on Arbitrariness and the Death Penalty

Arbitrariness in the imposition of the death penalty is exactly the type of thing the Constitution prohibits, as Justice Lewis Powell, Justice Potter Stewart, and I explained in our joint opinion in Gregg v. Georgia (1976). We wrote that capital sentencing procedures must be constructed to avoid the random or capricious imposition of the penalty, akin to the risk of being struck by lightning. Today one of the sources of such arbitrariness is the decision of state prosecutors—which is not subject to review—to seek a sentence of death. It is a discretionary call that may be influenced by the prosecutor’s estimate of the impact of his decision on his chances for reelection or for election to higher office.

(New York Review of Books, April 5, 2012.)

Transcript: My Interview With Retired Justice John Paul Stevens (excerpt)

By George Stephanopoulos

I sat down with retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens Wednesday in Washington, D.C. Stevens is out with a “Five Chiefs,” a memoir that chronicles his six decades on the court and his relationships with five different chief justices during that time. Here is the full transcript of the interview.

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: Justice Stevens, thanks for doing this.

JOHN PAUL STEVENS: Well, I’m happy to happy to meet you.

…

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: You of course, became an outspoken opponent of the death penalty in your time on the court. How did you evolve? Can you summarize how your own views evolved?

JOHN PAUL STEVENS: About the death penalty? Well, of course, it’s a long story, because I’ve been involved in that issue for so long. But there also you have to keep in mind, there are always two part to the question. One is, “When do you think it’s constitutional to have the death penalty?” And the other question is whether one thinks it’s a wise thing to do. And on the second question, whether your opponent is a matter of policy I’ve never felt that it was a particularly wise method of punishment. And several of the members of the court, I can say specifically Warren Burger and Harry Blackmun, although they voted to uphold the penalty consistently early on, they personally did not think it made sense.

But my own thinking on the issue, on the constitutional issue evolved over the years, after our first decision in 1975, in the first year that I came in the court, in which at which time I thought the court was adopting procedures and rules that would confine the imposition of the death penalty into a very narrow set of cases. And they took special pains to have fair procedures.

And over the years, the– I was disappointed to find they expanded the category of cases, rather dramatically later on, in ways that I don’t think Potter Stewart would have agreed with– who was sort of the principle author of our join opinion on– and they also have relaxed procedures in ways that actually give the prosecutor advantages in capital cases that I don’t think he has in ordinary criminal cases. And so that seemed to me there’s a change in the general atmosphere around capital cases that occurred over the years and made me–

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: It seems like there may be another evolution now in the country that the case of Troy Davis, executed last week. It appeared with the protests around that that the country may be heading towards a tipping point in another direction, against the death penalty. Is that what you see?

JOHN PAUL STEVENS: I don’t know. I’m not a very good judge of public reaction on something like that. But I think there always has been a significant group that felt that the penalty really wasn’t worth it and caused more harm than good.

(ABC News, Sep 29, 2011)

Retired Justice John Paul Stevens on His ‘Wrong’ Vote on Texas Death Penalty Case

By George Stephanopoulos

Retired Justice John Paul Stevens is a man of few regrets from his nearly 35 years on the Supreme Court, except one – his 1976 vote to reinstate the death penalty.

“I really think that I’ve thought over a lot of cases I’ve written over the years. And I really wouldn’t want to do any one of them over…With one exception,” he told me.

“My vote in the Texas death case. And I think I do mention that in that case, I think that I came out wrong on that,” Stevens said.

At the time he thought the death penalty would be confined “to a very narrow set of cases,” he said. But instead it was expanded and gave the prosecutor an advantage in capital cases, according to Stevens.

The retired associate justice has been an outspoken opponent of the death penalty, but his admission of that 1976 Jurek v. Texas vote comes at a time when the country appears to be revisiting its stance on the death penalty, in light of Troy Davis’ execution last week.

He writes in his book, “Five Chiefs,” that he regretted the vote “because experience has shown that the Texas statute has played an important role in authorizing so many deaths sentences in that state.”

In a recent Republican presidential debate there was a burst of applause after the moderator mentioned the 234 executions that occurred under Gov. Rick Perry. Stevens said he was “disappointed” when he saw that reaction.

“Maybe one believes, and certainly a lot of people sincerely do, that it is an effective deterrent to crime and will in the long run will do more harm than good. I don’t happen to share that view,” he said. “But there are obvious people who do. And, of course, being hard on crime has been– always– is politically popular, let’s put it that way.”

(ABC News, Sep 28, 2011)

An Open Mind on A Changed Court

Interview with Nina Totenberg, NPR

In an October 2010 interview on National Public Radio, then newly-retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens said he particularly regretted one vote during his 35 years on the high court—his 1976 vote to uphold the death penalty in Gregg v. Georgia. Stevens remarked, “I thought at the time … that if the universe of defendants eligible for the death penalty is sufficiently narrow so that you can be confident that the defendant really merits that severe punishment, that the death penalty was appropriate.” But, he added, over the years, “the Court constantly expanded the cases eligible for the death penalty, so that the underlying premise for my vote has disappeared, in a sense.” Justice Stevens also said that the court has made death penalty procedures more sympathetic to prosecutors: “I really think that the death penalty today is vastly different from the death penalty that we thought we were authorizing.”

The interview was conducted by NPR correspondent Nina Totenberg. She wrote more about Stevens’s views: “The court, he notes, has become more permissive in allowing prosecutors to object to seating jurors who have qualms about the death penalty. The result is that instead of getting a random sample of jurors, jury panels are more supportive of the death penalty. In addition, the court now allows the relatives of crime victims to testify during the penalty phase of a capital trial. These so-called victim impact statements were once ruled too incendiary to be permissible, but four years later, a more conservative court reversed the decision. All of this, says Justice Stevens, has changed the nature of the death penalty as he and the court envisioned it in the 1970s.”

(NPR,” October 4, 2010).

Supreme Court Justice Stevens Says U.S. “Better Off” Without Capital Punishment

During a “fireside chat” with fellow Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer and hundreds of lawyers and judges who practice in federal courts in Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin,

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens stated, “I think this country would be much better off if we did not have capital punishment.” Stevens noted that he believes the death penalty is constitutional, adding, “But I really think it’s a very unfortunate part of our judicial system and I would feel much, much better if more states would really consider whether they think the benefits outweigh the very serious potential injustice, because in these cases the emotions are very, very high on both sides and to have stakes as high as you do in these cases, there is a special potential for error. We cannot ignore the fact that in recent years a disturbing number of inmates on death row have been exonerated.” The “fireside chat” was part of the 7th Circuit Bar Association dinner in Chicago. Justice Stevens and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Sandra Day O’Connor have all voiced concerns about the death penalty in recent years, but this is perhaps one the most pronounced statements against capital punishment made by a Supreme Court justice since the late Harry Blackmun, who wrote in 1994, “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.”

(Chicago Sun Times, May 12, 2004).

Justice Stevens Addresses Death Penalty for Juveniles

U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens addressed the issue of juveniles and the death penalty while speaking at the 9th Circuit’s Judicial Conference on July 18, 2002. Justice Stevens, who wrote the majority opinion in Atkins v. Virginia abolishing the death penalty for those with mental retardation, predicted that juveniles would be the “next area for debate.” The United States is “out of step with the views of most countries in the Western world,” according to Stevens. Stevens did not anticipate that the Supreme Court would lead the debate and cautioned: “That is more likely to be addressed in the legislative forum than in the judicial forum.” Stevens also said that the public was growing more skeptical of the death penalty’s deterrent effect and more aware of the possibility that innocent people might be executed.

(Washington Post, Aug. 5, 2002)

“I think this country would be much better off if we did not have capital punishment.” — U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens

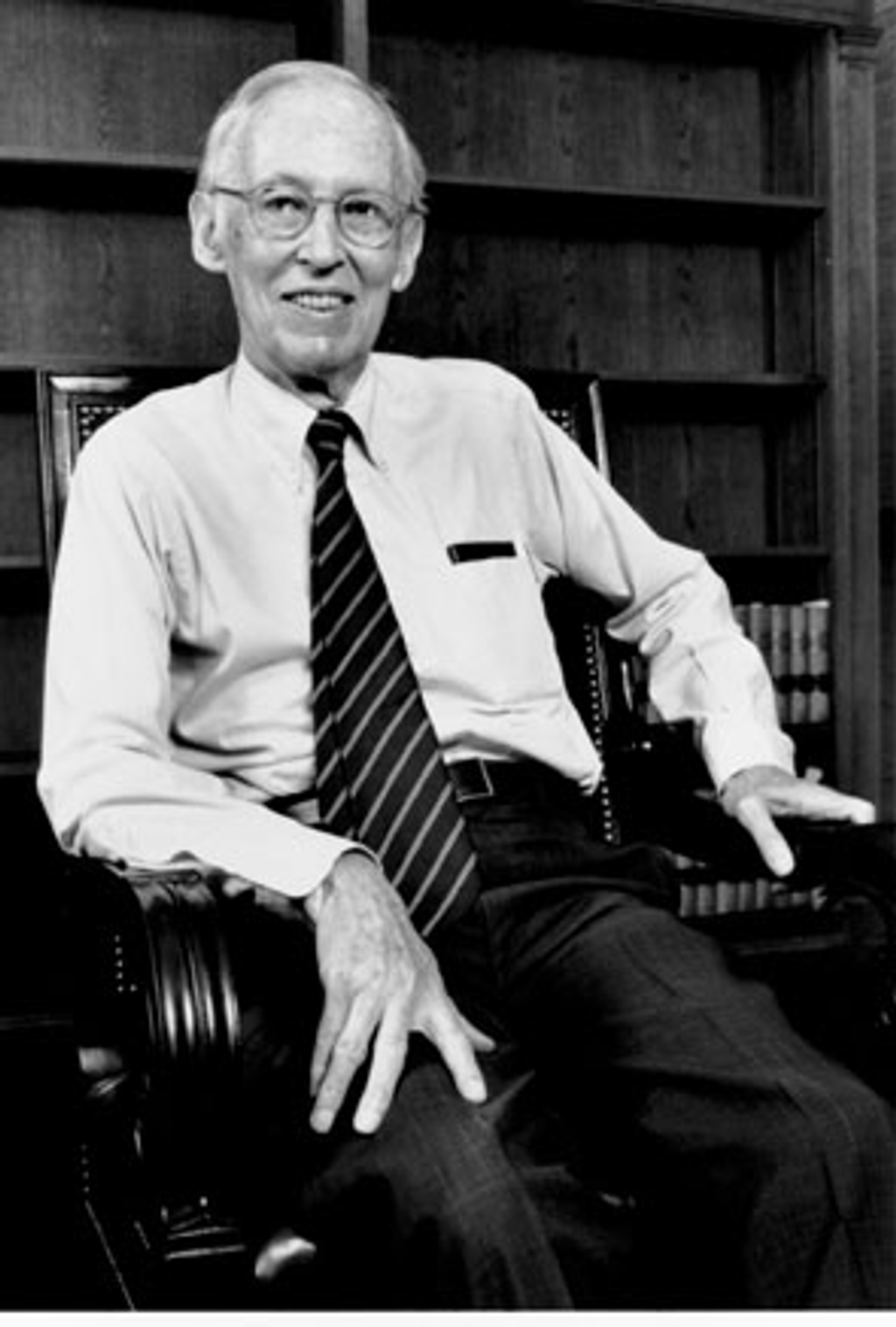

Justice Lewis Powell (Deceased) on the Death Penalty

Justice Lewpowellis Powell was appointed to the Court by President Nixon in 1972. He voted to uphold the constitutionality of the death penalty in 1972 and 1976. He later stated in an interview to his biographer:

“I have come to think that capital punishment should be abolished.” He stated that he would have changed his vote in capital cases, particularly McCleskey v. Kemp (racial bias in the death penalty) and that the death penalty “serves no useful purpose.”

(J. Jeffries, “Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr.” 451-52, 1994.)

Justice Harry Blackmun (Deceased) on the Death Penalty

In an interview in 1993 on the ABC News program “Nightline,” Justice Harry Blackmun said he was reconsidering his views on the death penalty and was “not sure” that courts could administer it fairly. Ultimately, Blackmun expressed his views in a dissent in a capital case, Callins v. Collins (1994), in which he concluded that “the death penalty experiment has failed.”

(L. Greenhouse, “Death Penalty Is Renounced By Blackmun,” N.Y. Times, Feb. 23, 1994).